| "Voices of the Dead" |

| (Part 2) |

| by Christopher Smith ("The Salt Lake Tribune", March 13, 2000) |

| Like a grim jigsaw puzzle, University of Utah forensic anthropologist Shannon Novak has pieced together the results of crime and warfare, meticulously re-assembling the bones of people who met violent ends. More........ |

|

|

|

| Her expertise has taken her to the mass graves of Croatia, where she joined a team of other experts in gathering evidence for prosecution of Serbian war crimes. She recently deciphered the bones of soldiers found on the bloodiest battlefield of Britain's Wars of Roses in 1461, questioning the romantic views of chivalry in medieval battle. |

| The situations are frequently tense, the work is tedious and the results are never pretty. But always, the truth ends up in sharper focus. |

| "Typically with history, the winning side writes the story," Novak says.. "This is giving the dead a chance to speak." |

| She took that same sense of purpose into a Utah polemic that began last summer. While The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was working to rebuild a monument to victims of the 1857 Mountain Meadows massacre, the skeletal remains of at least 29 slain emigrants were accidentally dug up by a church contractor on Aug. 3. |

| That scientists were required to study the bones of the massacre victims before they could be returned to their resting-place became the flash point in a five-week struggle that ended with a private reburial ceremony Sept. 10. The studies, normally required by state law of all accidentally discovered human remains, were terminated prematurely after Gov. Mike Leavitt personally intervened. |

| In a message to state antiquities officials, Leavitt wrote that he did not want controversy to highlight "this sad moment in our state's history and the rather good-spirited attempt to put it behind us." |

| Novak, along with a handful of other scientists, archaeologists and state antiquities officials, got caught in a political tug-of-war that pitted the need for scientific inquiry against the desire to respect the wishes of some descendants, who viewed the analysis as adding insult to injury. |

| "Arkansas people have two virtues -- caring for the sick and respecting the dead," Burr Fancher, a direct descendant of the massacre victims, wrote Aug. 24 to Brigham Young University's Office of Public Archaeology, which subcontracted with Novak to conduct the forensic analysis. "One of our fundamental beliefs has been grossly violated so that a few people could play with bones and for what reason? Everyone knows who was buried there and every serious student of history knows why it happened." |

| Yet at the same time, there is little widespread public knowledge of a crime of civil terrorism that pales in modern U.S. history only to the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing. The slaughter of an estimated 120 white civilians by a cabal of Mormon zealots and Indians is never mentioned in school history textbooks and is not even listed as a "point of interest" on Utah's official highway map. Until recent additions, the interpretive signs at Mountain Meadows were so vague as to how the Arkansas emigrants died that they became a source of national ridicule. |

| "All across the United States, when the dominant group has committed wicked deeds, historical markers either omit the acts or write of them in the passive voice," James W. Loewen writes in his new book, Lies Across America, which devotes a chapter to Mountain Meadows. "Thus, the landscape does what it can to help the dominant stay dominant and the rest of us stay ignorant about who actually did what in American history." |

| When the serene landscape at Mountain Meadows suddenly yielded hard evidence of one of the most gruesome crimes of western settlement, debate erupted over the need to delve further. |

"It is not important we know exactly how these people were murdered; we already know they were killed," says Weber State University history professor Gene Sessions, a Mountain Meadows scholar who serves as the president of the Mountain Meadows Association. "There's nothing those bones could show us that we don't already know from the documentary evidence."

But others disagree. |

| "Those bones could tell the story and this was their one opportunity," says Marian Jacklin, a U.S. Forest Service archaeologist in Cedar City. "I have worked with many of these descedants for years and understand their feelings. But as a scientist, I would allow my own mother's bones to be studied in a respectful way if it would benefit medicine or history." |

| Kevin Jones, state archaeologist, was overruled in his efforts to adhere to the state law requiring a basic analysis of the remains. |

| "The truth has never been fully told by anyone and there's plenty of information we could have learned here," he says. "We know they were murdered, but we don't know the details. And none of these people today can speak for every one of those people buried there." |

| Before the bones were placed back into the earth in the wake of the abrupt change in a state antiquities permit, they had started to reveal their secrets. In a 30-hour, round-the-clock forensic marathon, Novak and her students at the U. managed to reassemble several of the skulls before BYU officials arrived early on the morning of Sept. 10 to take the bones away. |

Her results, which are still being compiled for future publication in a scientific journal, confirm much of the documentary record. But they also provide chilling new evidence that contradicts some conventional beliefs about what happened during the massacre.

For instance, written accounts generally claim the women and older children were beaten or bludgeoned to death by Indians using crude weapons, while Mormon militiamen killed adult males by shooting them in the back of the head. However, Novak's partial reconstruction of approximately 20 different skulls of Mountain Meadows victims show: |

| |

-- At least five adults had gunshot exit wounds in the posterior area of the cranium -- a clear indication some were shot while facing their killers.. One victim's skull displays a close-range bullet entrance wound to the forehead; |

| |

|

| |

-- Women also were shot in the head at close range. A palate of a female victim exhibits possible evidence of gunshot trauma to the face, based on a preliminary examination of broken teeth; |

| |

|

| |

-- At least one youngster, believed to be about 10 to 12 years old, was killed by a gunshot to the top of the head. |

| |

|

| Other findings by Novak from the commingled partial remains of at least 29 individuals |

| |

|

| |

-- a count based on the number of right femurs in the hundreds of pieces of bone recovered from the gravesite -- back up the historical record; |

| |

|

| |

-- Five skulls with gunshot entrance wounds in the back of the cranium have no "beveling," or flaking of bone, on the exterior of the skull. This indicates the victims were executed with the gun barrel pointing directly into the head, not at an angle, and at very close range; |

| |

|

| |

-- Two young adults and three children -- one believed to be about 3 years old judging by tooth development -- were killed by blunt-force trauma to the head. Although written records recount that children under the age of 8 were spared, historians believe some babes-in-arms were murdered along with their mothers; |

| |

|

| |

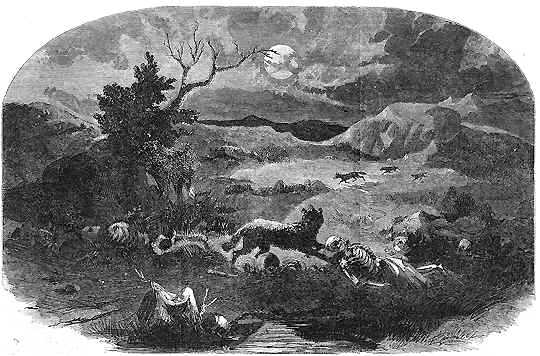

-- Virtually all of the "post-cranial" (from the head down) bones displayed extensive carnivore damage, confirming written accounts that bodies were left on the killing field to be gnawed by wolves and coyotes. |

|

| |

Assisted by graduate student Derinna Kopp and other U. Department of Anthropology volunteers, Novak's team took photographs, made measurements, wrote notes and drew diagrams of the bones, all part of the standard data collection required by law.

"I treated this as if it were a recent homicide, conducting the analysis scientifically but with great respect," says Novak. "I'm always extremely conservative in my conclusions. I will only present what I can verify in a court of law." |

| Beyond the cause of death, Novak was able to discern something about the constitution of the emigrants. |

| "These were big, strong, robust men, very heavy boned," she says. "We found tobacco staining on teeth, which is helpful in indicating males, and lots of cavities, indicating they had a diet heavy on carbohydrates." |

| There came a point in the reconstruction where the disparate pieces of bones slowly began to morph into individuals, each with distinct characteristics. One victim had broken an arm and clavicle that had healed improperly. One male had likely been in a brawl that left a healed blunt wound on the back of his head. One youngster's remains all had a distinctive reddish tint; as scientists inventoried the bones they would note another part of "red boy." |

| "We were at the stage when we were distinguishing them as people, where you were getting to know each one," says Novak. "We could have started to match people up. You would never have gotten complete individuals, but given a little more time, we could have done a lot more." |

But time was up. Novak had concentrated her initial work on the "long bones," as part of an agreement reached between the Division of History, Mountain Meadows Association and Brigham Young University. Those post-cranial remains would be re-interred during a Sept. 10 memorial. Because the reconstruction of the skulls would not be finished by then, the agreement allowed Novak until spring -- about six months -- to do the studies required by state law. |

| It was late on Sept. 8 that she learned that Division of History Director Max Evans had overruled Jones and re-wrote BYU's antiquities permit, changing the standard requirement for analysis "in toto" to require reburial of all remains on Sept. 10. When BYU asked to pick up the cranial bones on Sept. 9, Novak deferred, saying she had until the next day according to the amended permit. |

| "It was the only stand I could make because they had changed the rules in the middle of the process with no notice whatsoever," she says. "We worked through the night to get as much done as we could. This data had to be gathered." |

| BYU archaeologist Shane Baker picked up the remains from Novak early on the morning of Sept. 10, drove them to a St. George mortuary where they were placed in four small wooden ossuaries and then reburied later that day at the newly finished monument. |

| The dead would say no more. Their remains should never have been queried in the first place, says Weber State historian Sessions. |

"This idea of Shannon Novak needing six months to mess around with the cranial stuff, well, I know something about that science and that's a fraud," says the Mountain Meadows Association president, who adds he consulted his WSU colleagues about the time needed for such studies. "I really disagree with anyone who says we should have kept the bones out of the ground longer to determine what happened at Mountain Meadows. The documentary evidence is overwhelming. Whether or not little kids were shot in the head or mashed with rocks makes no difference. They were killed."

But other historians, searching for more information about an event cloaked in secrecy for generations, see value in the empirical evidence that forensic anthropology can offer. On Feb. 15, BYU's Baker made an informal presentation of his own photographs and research on the Mountain Meadows remains to the Westerners, an exclusive group of professional and amateur historians who meet monthly. As Baker flashed color slides of the bones on the screen, the men were visibly moved. |

"I've dealt with this awful tale on a daily basis for five years, but I found seeing the photos of the remains of the victims profoundly disturbing," says Will Bagley, whose forthcoming book on the massacre, Blood of the Prophets, won the Utah Arts Council publication prize. "It drove home the horror." |

But would it convince those who still believe the killing was done solely by Indians, or was part of an anti-Mormon conspiracy or the work of a single, renegade apostate?

"My own father believed John D. Lee was the one behind it all and if you think you were going to convince him any differently with empirical proof, forget it," says David Bigler, author of Forgotten Kingdom and former member of the Utah Board of State History. |

"People want to have the truth, they want it with a capital T and they don't like to have people upset that truth. True believers don't want to think the truth has changed."

And according to the leader of the modern Mormon church, the truth has already been told about Mountain Meadows. Back to top of page....... (Part 1) |